Creating a Culture of Listening

Certainly part of why Steve Jobs “always got it right” was that he was a genius. You can’t operationalize or imitate genius. But genius was only part of the story; there are plenty of geniuses with brilliant ideas who can’t turn them into anything tangible. More important than genius was the way, Steve led people at Apple to execute so flawlessly without telling them what to do.

This is something you can operationalize and imitate. To do it, though, you’ll have to push yourself and your team further out on the Challenge Directly axis of Radical Candor than will probably be immediately comfortable.

In fact, both Google and Apple achieved spectacular results without a purely autocratic style. This leads to important questions: how did everyone in the company decide what to do? How did strategy and goals get set? How did the cultures at these two companies, so strong and so different, develop?

How did tens of thousands of people come to understand the mission? It played out very differently at both companies — more orderly at Apple, more chaotic at Google — but at a high level, the process was the same.

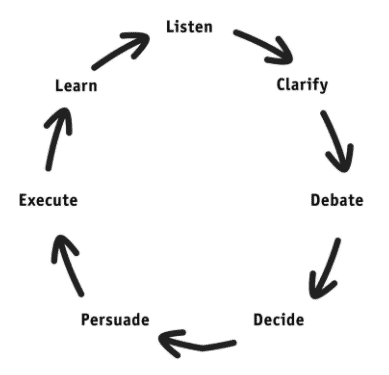

The process, which I call the Get Stuff Done (GSD) wheel, is relatively straightforward. But the key, often ignored by people who think of themselves as Get Stuff Done people, is to avoid the impulse to dive right in.

Instead, you have to first lay the groundwork for collaboration. When run effectively, the GSD wheel will enable your team to achieve more collectively than anyone could ever dream of achieving individually — to burst the bounds of your brain.

First, you have to listen to the ideas that people on your team have and create a culture in which they listen to each other. Next, you have to create space in which ideas can be sharpened and clarified, to make sure these ideas don’t get crushed before everyone fully understands their potential usefulness. But just because an idea is easy to understand doesn’t mean it’s a good one.

Next, you have to debate ideas and test them more rigorously. Then you need to decide — quickly, but not too quickly. Since not everyone will have been involved in the listen-clarify-debate-decide part of the cycle for every idea, the next step is to bring the broader team along.

You have to persuade those who weren’t involved in a decision that it was a good one so that everyone can execute it effectively. Then, having executed, you have to learn from the results, whether or not you did the right thing, and start the whole process over again.

That’s a lot of steps. Remember, they are designed to be cycled through quickly. Not skipping a step and not getting stuck on one are equally important. If you skip a step, you’ll waste time in the end. If you allow any part of the process to drag out, working on your team will feel like paying a collaboration tax, not making a collaboration investment.

You may very well be in a situation where your boss is skipping steps and just telling you what to do. Does that mean you have to do the same with your team? No, of course not! You can put these ideas into practice with the people who report to you even if your boss doesn’t subscribe to this method of getting things done.

When your boss sees the results, things may change. But, if they don’t, you may have to change jobs. When more people insist on a positive working environment, not only will results for your company improve, your happiness will as well.

So, how do you get started? The first step is to listen more and talk less.

Listen

Give the quiet ones a voice.”

— JONY IVE

You already know you’re supposed to listen, and you probably already know how (and how not) to listen. The problem is that when you become the boss, people are predisposed to tell you that you must totally change your style of listening, and you can’t do that.

The good news is you can stick to your own style and still make sure that everyone on your team gets heard and is thus able to contribute. Jony Ive, Apple’s chief design officer, once said at an Apple University class that a manager’s most important role is to “give the quiet ones a voice.” I love this.

Google CEO Eric Schmidt took the opposite approach, urging people to “Be loud!” I love this, too.

The two leaders took different approaches to ensure that everyone was heard. This is your goal as well, but there is more than one way to achieve it. You have to find a way to listen that fits your personal style, and then create a culture in which everyone listens to each other so that all the burden of listening doesn’t fall on you.

Quiet Listening

Tim Cook, Apple’s CEO, is the master of silence. Before I interviewed at Apple, a friend warned me that Tim tended to allow long silences and that I shouldn’t let it unnerve me or feel the need to fill them. Despite this warning, in our first interview I reacted to a long period of silence by anxiously talking nonstop, and in the process inadvertently told him far more about a mistake I’d made than I had intended. Just when I realized, panic-stricken, that I was about to reveal something that might well cost me the job, the room began to shake.

“Earthquake?” I asked, with what I suspect was undisguised relief. Tim nodded, looking up at the movement of the walls. “Pretty good-sized one too, I’d say.”

Seizing the chance to listen rather than talk, I asked about the building’s design, which the engineer in Tim couldn’t resist describing to me. Because the building was on top of rollers, the earthquake’s movement felt more pronounced; scarier but safer.

Tim smiled at the contradiction. Following in Tim’s footsteps, one of my students in the Managing at Apple class said that he tried to make sure to spend at least 10 minutes in every one-on-one meeting listening silently, without reacting in any way. He would keep his facial expression and body language totally neutral.

“What did you learn in that 10 minutes that you didn’t learn the other 50?” I asked.

“I heard the things I didn’t want to hear,” my student said, validating Tim’s technique. “If I gave any reaction at all, people would often tell me what they thought I wanted to hear. I found that they were much more likely to say what they really thought — even if it wasn’t what I was hoping to hear — when I was careful not to show what I thought.”

There are real advantages to quiet listening, but it also has a downside. When you’re the boss and people don’t know what you think, they waste a lot of time trying to guess. Some will even use your name in vain — “Well, what the boss wants to do is X” — and then go on to describe what they want to do instead.

And since nobody can be sure what you really think, they can sometimes get away with it. In addition, plenty of people are made very uncomfortable by silence, as the examples above demonstrate.

It can feel like playing a high-risk poker game instead of having a Radically Candid conversation. Some people feel a quiet listener is not listening at all but instead setting a trap: waiting for others to say the wrong thing so they can pounce.

If you’re a quiet listener, then, you need to take steps to reassure those made uncomfortable by your style. Don’t be pointlessly inscrutable. To get others to say what they think, you need to say what you think sometimes, too.

If you want to be challenged, you need to be willing to challenge. The manager in my class was expressionless for only 10 minutes of his 1:1s, not the full hour. If he’d been utterly expressionless the whole time, it would have been hard for people to trust him or to relate to him.

Tim Cook wasn’t always silent either, of course. But because he was generally so quiet, people leaned forward to listen to what he said. And when he spoke, albeit very quietly, his thinking was always crystal clear. Quiet listening clearly works for many managers, but I cannot pull it off. Luckily, there is another model.

Loud Listening

If quiet listening involves being silent to give people room to talk, loud listening is about saying things intended to get a reaction out of them. This was the way Steve Jobs listened. He would put a strong point of view on the table and insist on a response. Why do I call this listening, instead of talking, or even yelling? Because Steve didn’t just challenge others; he insisted that they challenge him back.

Obviously, this approach works only when people feel confident enough to rise to the challenge. Just as some people are freaked out by quiet listening, other people are offended by loud listening. If you are a loud listener, how do you deal with people who are either constitutionally unable to stand up to an aggressive boss or whose position is too marginal to allow them to feel secure, even if the larger culture welcomes this behavior?

How do you listen to a person who has just started at the company and doesn’t feel established enough to take a high-profile stand? That person might know a good reason why you are wrong. And yet they won’t speak up. If you have a loud listening style, you need to go to some lengths to build the confidence of those whom you’re making uncomfortable. And as people witness one another challenging the boss, they will grow to feel it’s safe to do so as well.

Jony Ive said that Steve would often come to him and say, “Jony, here’s a dopey idea…” He wasn’t quiet about his idea, but he was inviting Jony to challenge it by calling it dopey.

Randy Nelson, the dean of Pixar University and a faculty member at Apple University, captured this when he said of Steve Jobs, “He’s a lion. If he roars at you, you’d better roar back just as loudly — but only if you really are a lion, too. Otherwise, he’ll eat you for lunch.”

Steve didn’t surround himself with people who’d tell him when he was wrong by making everybody feel comfortable. The people who worked closely with him knew they had better speak up when they saw a problem or a flaw in his logic, or face his wrath later. This didn’t mean they had to be loud themselves. Steve worked really well with both Tim Cook and Jony Ive and both of them were quiet listeners. But they did have to be strong and super confident.

You don’t have to adopt Steve’s style to be a loud listener. Paul Saffo, an engineering professor at Stanford, describes a technique he calls “strong opinions, weakly held.” Saffo has made the point that expressing strong, some might say outrageous, positions with others is a good way to get to a better answer, or at least to have a more interesting conversation.

I love this approach. I’ve always found that saying what I think really clearly and then going to great lengths to encourage disagreement is a good way to listen. I tend to state my positions strongly, so I have had to learn to follow up with,

“Please poke holes in this idea — I know it may be terrible. So tell me all the reasons we should not do that.”

Once I put a “you were right, I was wrong” trophy on somebody’s desk after her position on something proved to be correct and mine dead wrong.

Loud listening — stating a point of view strongly — offers a quick way to expose opposing points of view or flaws in reasoning. It also prevents people from wasting a lot of time trying to figure out what the boss thinks.

Assuming that you are surrounded by people who don’t hesitate to challenge what you say, stating it clearly can be the fastest way to get to the best answer.

Perhaps most important is to stick to the style that feels most natural to you. Many leadership books push for quiet listening. But if you’re a loud listener, it’s really hard to follow that advice. Attempting to behave in ways that feel deeply unnatural can make your team feel less comfortable with you rather than more so.

Instead, try to strengthen your awareness of how your style makes your colleagues feel and work on improving that dynamic.

Figure out how to listen to give the quiet ones a voice without weirding out their louder colleagues. You don’t want a tyranny of the most verbose on your team; you want to get to the best answer together. (Listen to our podcast episode about quiet versus loud listening.)

Create a Culture of Listening

It’s hard enough to get yourself to listen to your team members and let them know you are listening; getting them to listen to one another is even harder.

The keys are:

1. Have a simple system for employees to use to generate ideas and voice complaints,

2. Make sure that at least some of the issues raised are quickly addressed, and

3. Regularly offer explanations as to why the other issues aren’t being addressed.

This system should not merely empower anyone to point out things that could be better but also enable others to help fix those things or make changes. You have to agree to let them ask you for some help and to champion the system enthusiastically.

Define clear boundaries of how much time you can spend — and then make sure that time is highly impactful.

At Google, people constantly came to me with good ideas — more than I could handle, in fact — and it became overwhelming. So I organized an “ideas team” to consider them. For context, I circulated an article from Harvard Business Review that explained how a culture that captures thousands of “small” innovations can create benefits for customers that are impossible for competitors to imitate.

One big idea is pretty easy to copy, but thousands of tweaks are impossible to see from the outside, let alone imitate.

Next, I talked through some key principles that ought to guide the ideas team, first among them empowerment. The ideas team had to commit to listening to any idea that anyone brought to them, to explain clearly why they rejected the ideas they rejected, and to help people implement ideas that the ideas team deemed worthwhile. If somebody’s idea seemed especially promising, they could even negotiate with the person’s manager to give them some time off from their “day job” to work on implementing it.

They were encouraged to assign me up to three action items a week. After this innovation, instead of feeling stressed whenever I would hear a cool idea in a meeting or receive an inspired email, I could react enthusiastically and delegate it to the ideas team.

Soon, lots of people were submitting ideas they had for improving the product, growing the business, and making our processes more efficient. We created an ideas tool (basically just a wiki) that allowed people to submit an idea, have it reviewed by the team, and voted up or down.

That was a form of listening, and people whose ideas got voted up definitely felt heard by their colleagues. People whose ideas were not voted up knew that their ideas had been explicitly rejected: a much clearer signal than radio silence from overburdened management. However, a vote is not always the best way to identify the best ideas or to make sure people are listening to each other.

Therefore, I asked the ideas team to read all the ideas and talk to all the people who submitted them — to listen. After that development, the team used a combination of votes and judgment to select the best ideas.

More importantly, the ideas team helped people get the selected ideas implemented. Occasionally this was about getting time for people to work on them, or getting some input from me, but often all it took was just the validation and encouragement that came from listening and responding. “Yes, that’s a cool idea! Do it!”

Sarah Teng, a recent college graduate on the AdSense team, came up with the idea of using programmable keyboards to create shortcuts for phrases or paragraphs they used over and over when communicating with customers. It seemed like a good idea, so the ideas team asked me to approve the budget to buy programmable keypads. I did as they asked, and this simple idea increased the global team’s efficiency by 133 percent.

This meant that everyone on the team had to spend far less time typing the same damn words over and over and had more time to come up with other good ideas — a virtuous cycle. Bam!

When Sarah presented her project to the team, I didn’t just thank her; I also showed a graph of how this idea would improve our efficiency over time. But efficiency is not what people cared most about, so I also stressed to the team how her innovation would make people’s jobs more fun and help them grow in their careers since they’d get to spend less time doing grunt work and more time doing work they found interesting.

I explained that Sarah would have an opportunity to share her idea with leaders from another, much larger team, for an even larger impact. And I sent around again the HBR article showing how competitive advantage tends to come not from one great idea but the combination of hundreds of smaller ones.

Why did I add all that context? First, to demonstrate just how great the impact of her idea was. The use of programmable keypads by itself was hardly revolutionary, but when people saw the cumulative effect of that idea and others like it over time, Sarah’s innovation felt a lot bigger.

Second, it inspired people who had other ideas like this to be vocal about them. Third, and most importantly, it encouraged people to listen to each other’s ideas, to take them seriously, and to help one another implement them without waiting for management’s blessing. It’s so easy to lose “small” ideas in big organizations, and if you do you kill incremental innovation.

Hundreds of really smart people had been working in online sales and operations for years. It was hard for me to believe that nobody else had ever had the programmable keypad idea before, but if they had, management hadn’t listened.

If you can build a culture where people listen to one another, they will start to fix things you as the boss never even knew were broken.

Most meaningful to me was that morale on the team soared. At one point the “Googlegeist” survey on employee morale showed that the team of people who were answering customer support emails for AdSense felt much better about the role that innovation played in their work than the engineers working on Search did — despite the fact that those engineers were probably some of the most creative engineers in the world.

Sometimes creating a culture of listening is simply a matter of managing meetings the right way. When just a couple of people were doing all the talking at a meeting, I’d stop and go around the table to ensure that everyone got heard. Other times, I would stand up in the next meeting and walk around, physically blocking a person who was talking too much.

Sometimes I’d have a quick conversation with people before a meeting, asking some to pipe up and others to pipe down. In other words, part of my job was to constantly figure out new ways to “give the quiet ones a voice.”

Adapt to a Culture of Listening

My friend Astrid Tuminez has a great story about how important it is to adapt to a culture of listening in a new situation. She grew up in a tiny fishing village in the slums of the Philippines but went on to have a career that spanned Moscow (where I worked with her), New York, and Singapore.

While working at the U.S. Institute of Peace, she was invited to work on the peace process with the Moro Islamic Liberation Front in the southern Philippines. When she first arrived, she acted like a New Yorker — very businesslike, making back-to-back appointments.

Then a member of the Philippine negotiating team told her that someone from the Muslim/Moro group had sent a note to Manila saying, “Who is this woman and what planet is she from?” The person who gave Astrid feedback was particularly invested in Astrid’s success because they had connected over the fact that they were from the same province.

To the Muslims, Astrid had come across as unfeeling, inhospitable, and foreign (even though she was Filipino and could speak Filipino). Thinking it over, she realized that she’d made some significant mistakes — such as hosting meetings with people without offering them real food, which was so important in the culture.

She spent the next few months listening and making only “loose” appointments. She attended public events and made the rounds without scheduling people back-to-back. And she made sure she had a lot of food available when she hosted meetings.

By taking time to get to know people and by just listening she was able to build trust and show she cared deeply about the peace process. Eventually, the Moros became very willing to speak to her and to take her places where other outsiders couldn’t or wouldn’t go. It made all the difference in her ability to be effective in the complex and nuanced negotiations her job required.

Originally published on Radical Candor